- Oct 28, 2022

- 6 min read

How Money Is Laundered Through Football

As the World Cup approaches, Sumsub is here to detail the serious threat posed by money laundering and how the international community can mitigate it.

There are many ways to make money on sports: from sports betting to sponsorships to action figures. These activities can be very profitable—and the higher the profit, the higher the risk of money laundering.

According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global anti-money laundering watchdog, the most vulnerable sports include football, cricket, rugby, horse racing, motor racing, ice hockey, volleyball and basketball.

Since the 2022 World Cup is right around the corner, Sumsub’s experts are here to go over the difficulties modern sports face with a focus on football—the most watched sport in the world.

Why is football especially prone to money laundering?

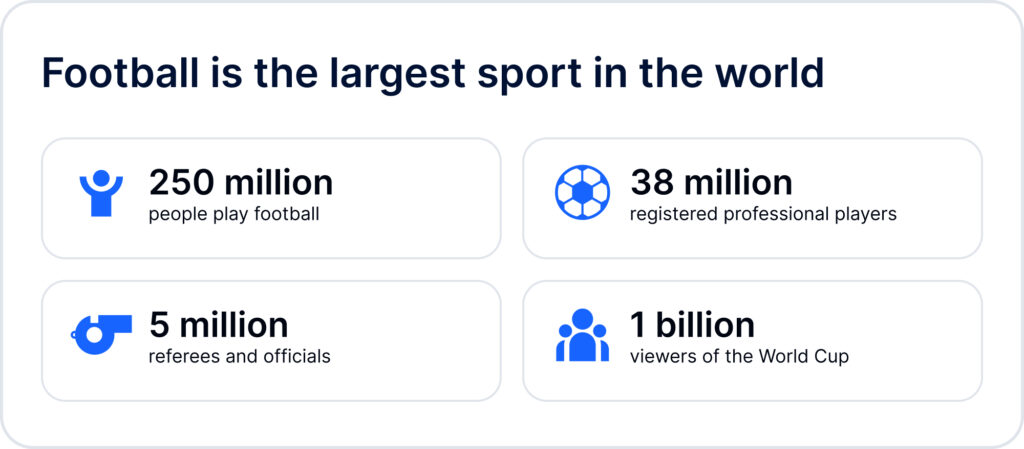

Football is the biggest sport in the world: approximately 250 million people play it, there are around 38 million registered professional players, 5 million referees and officials. It’s also the most watched sport in the world, with around 1 billion tuning into the World Cup alone.

Football is also a cash-rich sport that attracts global investors across all sectors of the economy—including those which aren’t quite legal. The reason for this stems from a lack of global AML regulations in sport (this does not include sports betting, which is regulated in most countries).

How football is exploited by criminals

There are many ways that illicit funds can make their way into football, with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimating that about $140 billion is laundered through the sport per year. This includes:

Purchase and sale of football clubs:

Those seeking to launder their funds can do so by acquiring an entire football club. Indeed, many clubs are managed by amateurs, which have poor finances management and possibly debts, and therefore can easily be acquired by dubious investors, according to the OECD.

The World Cup is the hardest time for bookmakers due to user traffic spikes. Find out what it is and how to cope with it here.

Player trades

Just like with other common money laundering methods, including art or real estate, the worth of a player can be greatly overvalued.

In 2014, the Bucharest Court of Appeal in Romania handed down jail sentences for eight executives and management officials (including former FC owners and agents), who were found guilty of tax evasion and money laundering involving the transfer of football players between international football clubs. As a result, Romania lost 1.7m euros ($1.6m) in taxes.

In 2020, it was reported that several agents organized fake transfers through a Cyprus football club, Apollon, to evade taxes and launder money.

Football agents

Of course, inflated agent fees are one way to clean dirty money. However, agents can also be extremely influential in football clubs, with close connections to key members. From such positions of power, agents can also be involved in more complex ML schemes.

In 2019 a corrupt football agent claimed he had “thanked” the former Manchester United manager for fixing a match by giving him a £30K ($34.7K) Rolex watch.

Player image rights

Contracts for the rights to use players’ images can get lucrative, which leads to various forms of financial misconduct:

- Money laundering through sales of media rights, and merchandise.

- Players may not declare part of the money received.

- The money received settles in a tax haven.

Forgery of ticket sales

Amateur clubs—and the ticket sales companies working with them—are especially prone to this. In comparison to major clubs, authorities are less inclined to check the number of spectators entering an amateur club’s stadium, which makes it possible to launder money through fake ticket sales.

Why is money-laundering extremely harmful for the sports sector?

Football suffers greatly from financial crime. For instance, if money is laundered via player trades, it obscures the players’ true competitive value. In other words, less talented players can get overpaid, while talented ones get underpaid. What’s more, if a club gets injected with criminal cash, they have no incentive to develop, because they already have ‘profit’.

Another devastating consequence is “match fixing,” where the outcomes of games are predetermined in order to move dirty money through betting activity. As Europol reports, organized crime groups can acquire football clubs to use as large-scale money laundering instruments through match fixing. If proven, this activity can ruin a club’s reputation. It can also undermine the trust of fans placing legitimate bets on matches.

The global annual criminal proceeds from betting-related match-fixing are estimated to be €120m ($116m) annually.

Suggested read: Sumsub’s global guide to gambling and betting

What measures do international organizations take to cope with money-laundering in football?

The European Union

In March 2007, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the future of professional football in Europe, in which the European Parliament asked the Council of the European Union to develop and adopt measures in the fight against the criminal activities haunting professional football.

In July 2007, the European Commission published its White Paper on Sport, which recognized that corruption, money laundering and other forms of financial crime affect sport at local, national and international levels. The White Paper proposed tackling crossborder corruption problems at the European level and monitoring the implementation of EU anti-money laundering legislation with regard to sport.

National authorities

Such bodies tackle corruption and money laundering in football on the country level. For example, France set up a Direction Nationale du Contrôle de Gestion (DNCG) which controls the finances of professional and amateur sporting clubs. DNCG is a voluntary body within the French Federation of Football consisting mainly of accountants and lawyers that warrants the “fairness in sports”.

There are similar associations in Italy and Brazil as well.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC)

The IOC Ethics Commission, created in 1999, is charged with defining and updating a framework of ethical principles, including a Code of Ethics. However, the IOC Code of Ethics advises that the financial support given by the IOC must be only for Olympic purposes. The committee monitors all betting activities on the 28 sports during the Olympic Games.

The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA)

UEFA runs a Europe-wide Fraud Detection System which monitors the domestic matches and national cup fixtures of all 53 UEFA-affiliated national associations for irregular betting patterns.

Local football associations

Some football associations pay close attention to money-laundering issues. For example, the English Football Association has an extensive guidance for football clubs called “Money Laundering and The Proceeds of Crime Act”.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has a number of recommendations to such associations, including establishing staff training on money-laundering legislation and appointing a money-laundering reporting officer internally.

Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA)

This is the heart of global football management, carrying a special responsibility to safeguard the integrity and reputation of football worldwide.

In November 2005, FIFA established a special task force “For the Good of The Game” to investigate and combat threats to the integrity of football. Since then, the organization has adopted the following measures aimed at fighting corruption and money-laundering in football:

- Player transfer matching system (details are available on the FIFA website);

- FIFA Club Licensing Regulations;

- Players’ Agents Regulations;

- Early warning system on betting activities (EWS);

- A clearing house for football transfers which was adopted after a series of high-profile corruption scandals in FIFA several years ago.

The problem with FIFA

Sadly, football’s international governing body is also famous for its corruption and money-laundering issues.

2015 was marked by the most high-profile FIFA scandal so far, when the US Justice Department unsealed a 47-count indictment charging 14 world soccer figures, including FIFA officials, with racketeering, bribery, money laundering and fraud totaling more than $150 million.

Following these revelations, the FATF said that “recent reports … underscore how important it is that financial institutions identify and monitor high-risk customers” and that financial institutions “do not appear to have given a sufficient amount of scrutiny to the financial activities of the officials concerned, as many of these allegedly corruption-related transfers passed through the international financial system undetected.”

However, soon the FATF deleted this statement due to “concerns about its phrasing” and a “lack of concrete evidence to support the claims”.

At the same time, several bank compliance officers expressed concern about the level of due diligence insports. Still, no new measures were taken at the time.

In 2018, a confidential UEFA-commissioned report, “Intermediation market and transfers in football,” concluded that money-laundering in football was widespread, and “dominant agents” were exploiting failures to enforce rules banning third-party ownership of clubs.

A summary of the 2018 report compiled by the Center for Sports Studies (CIES) for UEFA was never published, but was seen by the Guardian. It advised that third-party ownership of players’ economic rights, banned by FIFA in 2015, “is still a well-established reality.” The report also noted a lack of transparency in the payment of agent commissions, which allows for money laundering alongside tax evasion schemes. Indeed, payments are often made to tax havens, not only for the purposes of enriching agents but also to “the club owners and executives with whom they collaborate”, the report concludes.

Room for improvement

The CIES report made several recommendations to help rectify systemic issues in FIFA, including:

- to cap and tie the agent fee to the salary of the player, replacing the practice of commissions being paid as a proportion of the transfer fee.

This is something FIFA is about to implement in 2022, namely: 10% of the transfer fee for agents of releasing clubs, 3% of the player’s remuneration for player agents and 3% of the player’s remuneration for agents of engaging clubs.

- to prevent individuals with criminal records from registering as intermediaries;

- to establish an investigative body to examine disputes and cross-check the flow of money in transfers;

- to establish a clearing house through which all payments to agents should be made.

This measure is also about to be introduced in November 2022.

At the moment, FIFA’s clearing house is only used for payments associated with “training compensation and solidarity contribution”. But soon all agents’ commissions will be paid through it.

Other international watchdogs recommend building more awareness, better governance, and financial transparency.

Transparency International, for example, names various strategies available to counter money-laundering and the illegal financing of football clubs, including:

- establishing codes of conduct;

- introducing whistleblowing policies;

- setting up ethics committees;

- imposing sanctions;

- instituting training courses to raise awareness of fraud and corruption;

- ensuring accounts and records are audited;

- conducting “fit and proper person” tests for potential club owners.

Football is largely exposed to corruption and money laundering due to lack of centralized sporting regulations. However, after a number of serious scandals, necessary steps (such as introducing the new clearing house) are now being taken by international bodies like FIFA to fight back against corruption and money laundering.

Relevant articles

- Article

- Feb 3, 2026

- 11 min read

Arbitrage in Sports Betting & Gambling in 2026. Learn how iGaming businesses detect arbers using KYC & fraud prevention tools.

- Article

- Feb 5, 2026

- 20 min read

What is Sumsub anyway?

Not everyone loves compliance—but we do. Sumsub helps businesses verify users, prevent fraud, and meet regulatory requirements anywhere in the world, without compromises. From neobanks to mobility apps, we make sure honest users get in, and bad actors stay out.