- Jul 20, 2021

- 5 min read

What You Need to Know About Indonesia’s Incoming Data Protection Law

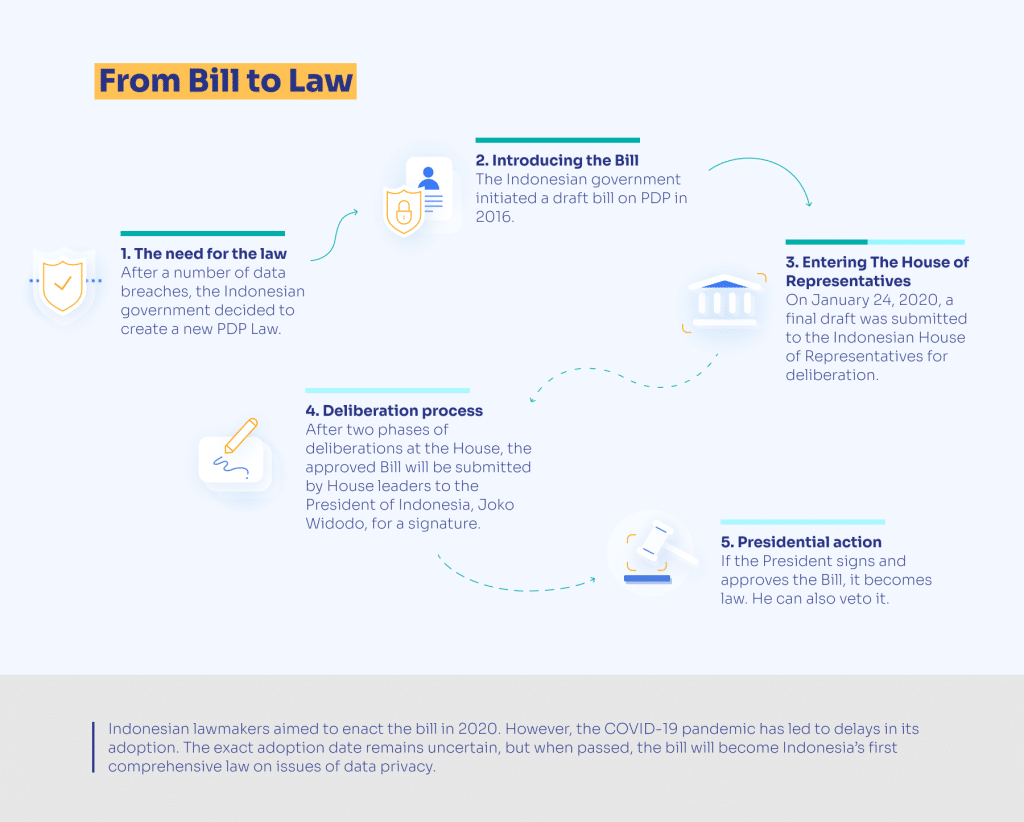

Indonesia is the largest and fastest-growing digital economy in Southeast Asia, expected to reach $130 billion by 2025. Now the country is close to passing its first personal data protection law (PDP Law), as Indonesia's parliament has again put the bill on the priority list for deliberation following delays due to COVID-19. This comes on the heels of a massive data breach in May 2021, involving the sale of personal data belonging to 279 million people.

The PDP Law is set to pass later this year, introducing new key roles, data ownership rights, data transfer rules, among other serious changes to Indonesian data protection legislation. Regulators plan on providing a two-year deadline for full compliance and recommend using the current draft of the law as a basis. We’ve summarized all the key points and updates in this article to help you ensure lasting compliance with the incoming PDP law.

Why should you read this?

In addition to setting new data protection standards in Indonesia, the PDP law will also be felt in jurisdictions all over the world—as any company, regardless of where it’s registered, will be subject to the PDP Law if it deals with Indonesian customers.

The PDP Law will bring considerable changes to how companies process Indonesians' personal data, including how and where this information must be processed and stored. Sanctions for non-compliance will be stiff, including fines of up to US$14.4 million. Therefore, companies should already be identifying and resolving any potential challenges to compliance with the PDP Law.

The current status of the PDP Law

The Personal Data Protection Law (PDP Law) is making its way through Indonesian Parliament and will soon bring much-needed changes to the country’s data privacy rules. The legislation is based on the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which means that Indonesia will soon follow nearly all the same data subject rights and personal data processing regulations as the EU.

The PDP Law has 72 articles across 15 chapters, covering data ownership rights, prohibitions on data uses, as well as the collection, storage, processing, and transfer of personal data.

Applicability

The PDP Law aims to protect all personal data belonging to Indonesian citizens, processed both electronically and manually. It will apply to any entity that handles the personal data of any Indonesian citizen anywhere in the world. These entities could be both public and private sector individuals and corporations located in Indonesia or abroad.

Current regulations

There is currently no general law on data protection in Indonesia. However, there are several specific laws that indirectly deal with data privacy. Currently, the Law on Electronic Information and Transactions is the main reference for personal data protection in Indonesia.

The new PDP Law is expected to apply to all sectors, bringing forward comprehensive provisions on personal data protection, both electronically and non-electronically.

What will the new law change

This section details the key incoming changes to Indonesian data protection rules. Click the titles for more information:

1. Defining Personal Data and Personal Data types

Current rules: There are no classifications of personal data.

Incoming rules: Two personal data classifications will be recognized:

- General: full name, gender, citizenship, religion, or any other personal data used to identify someone;

- Specific: financial data, health data, life/sexual orientation, biometric data, genetic data, political views, data on children, criminal record.

However, the PDP Law will not differentiate processing requirements between general and specific personal data.

2. Identifying key roles

Current rules: There is no difference between data controllers and processors. All parties that handle personal data have the same responsibilities, regardless of their actual role in data processing.

Incoming rules: The data controller and processor roles will be separated. Accordingly, the terms “Controller” and “Processor” will be introduced, carrying the same meaning as in the GDPR:

- Data controller: a party that determines the purpose of and controls the processing of personal data;

- Data processor: a party that processes personal data on behalf of the personal data controller.

*A “party” is any individual, corporation, public entity, business actor, organisation, or institution.

3. New data ownership rights

Current rules: The rights of personal data owners are not explicitly defined.

Incoming rules: Data owners will be granted eleven rights, similar to those recognised under the GDPR. These include data access, withdrawal approval, processing restrictions and objections, deletion requests, as well as the right to be informed and to sue and request compensation in case of any violations. Both data controllers and processors will be required to observe and respect these rights.

4. New cross-border data transfer regulations

Current rules: Foreign countries to which personal data is transferred are not required to meet certain criteria or have a certain level of personal data protection.

Incoming rules: Cross-border data transfers between controllers will be limited to countries and international organizations that have data protections equal to or higher than Indonesia. In addition, the receiving countries and international organizations must have:

- an agreement with Indonesia;

- a contract between personal data controllers that covers personal data protection matters;

- the consent of the personal data subject.

However, the above requirements will not apply to controller-to-processor personal data transfer.

5. Designating data protection officers

Current rules: Data controllers and data processors are not required to designate a data protection officer (DPO).

Incoming rules: Certain data controllers and processors will be required to designate a DPO, who ensures the security of all personal data handled. Controllers and processors must designate a DPO if:

- they process personal data for the purpose of providing public services;

- their main activities require regular and systematic monitoring of personal data on a large scale;

- their main activity consists of processing specific data, including criminal data, on a large scale.

Data protection officers will be appointed based on their professional qualifications, legal knowledge, and experience in data privacy. However, there are currently no specific mandatory qualifications, skills, or educational requirements. This may be clarified in the future.

6. Detailing data breach notification requirements

Current rules: Data breaches must be immediately reported to the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MCIT) and data owners must be notified within 14 days.

Incoming rules: There will be detailed requirements on reporting obligations, including that both the data owners and MCIT must be notified within 72 hours of a breach.

These notifications must detail:

- the compromised data;

- when and how the data was compromised;

- management and recovery efforts.

Data breaches are currently surging in Indonesia, which is why authorities are paying particular attention to them.

Sanctions

There will be two types of sanctions for non-compliance with the PDP Law—administrative (written warning, temporary suspension of processing of personal data, deletion of personal data, compensation, or administrative fines) and criminal (imprisonment, fines).

Criminal penalties for individuals range from 20 to 70 Billion Rp (from US$1.4 million to US$4,8 million) and/or imprisonment from 2 to 7 years, depending on the nature of the violation. Corporations, however, can see fines as high as 210 Billion Rp (US$14,4 million), in addition to confiscation of profits or assets, asset freezes, or closure of all or part of the business.

These sanctions can be applied to breaches of personal data privacy (selling or buying personal data, collecting personal data for personal gain, and so on). However, the draft PDP Bill doesn’t specify if or how the sanctions differ in severity based on the volume of data violated and the harm done.

How to comply

According to the current draft of the PDP Laws, entities that process personal data will be given a two-year period to achieve full compliance. During this transition period, you can prepare by:

- Supervising every party involved in data processing, maintaining records, reporting data breaches, ceasing to process data when data owners revoke consent, preventing unauthorized access to personal data, and supervising every party involved in processing.

- Analyzing how you currently handle personal data (including collection, storage, modification, publishing, destruction, etc.) and correcting existing PDP-related technologies to ensure that all necessary control measures are in place.

- Reviewing whether current contracts with customers and third-parties include all the necessary clauses, including the nature and purpose of data processing, duration, controller’s rights and obligations, etc.

- Checking reliable sources that post updated PDP requirements and standards, as well as designating an employee to handle compliance matters going forward.

- Getting outside help through specialized services and software solutions to help automate policy-related processes and stay notified on relevant regulatory changes.

We'll keep doing our best to help companies solve compliance and regulatory issues. And we’ll continue to update this article with all the latest PDP Law-related updates, so stay tuned.

Get some rest while Sumsub takes care of your compliance obligations. Talk to our team today.

Relevant articles

- Article

- Feb 11, 2026

- 8 min read

Digital trust is transforming Asia's digital economy in 2026. Explore trends in superapps, data sovereignty, IDV, and AI fraud prevention.

- Article

- 3 weeks ago

- 13 min read

How to check if a company is legit: a step-by-step guide for businesses and consumers covering registrations, licenses, reviews, and scam warning sig…

What is Sumsub anyway?

Not everyone loves compliance—but we do. Sumsub helps businesses verify users, prevent fraud, and meet regulatory requirements anywhere in the world, without compromises. From neobanks to mobility apps, we make sure honest users get in, and bad actors stay out.